by Isabel-Kai Fisher (they/them), Youth Advisory Board member

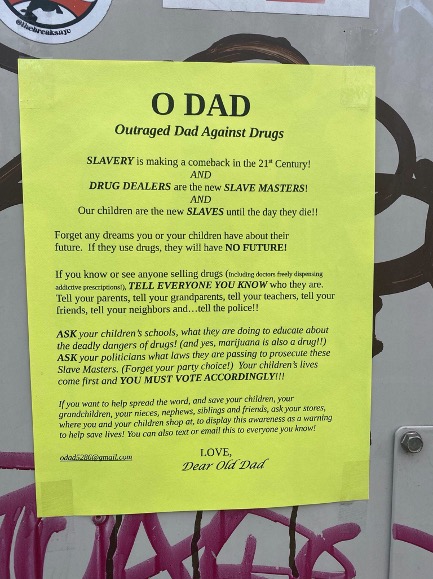

I came across this flyer on one of my routine walks to CVS in a Westchester County town in New York. It was taped to a graffitied-over electrical equipment box. I took a picture of it and then kept walking, feeling uncomfortable by the message, but unsure if there was anything I could do.

However, that evening, I decided to email “ODAD” a critique on his messaging; saying that I don’t think shame or blame is helpful and that reporting drug dealers/drug users to the police can often do more harm than good.

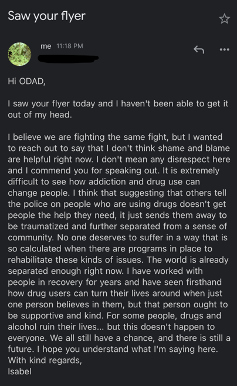

In ODAD’s reply the next evening, he made sure to clarify that drug dealers should be reported to everyone, not just the police:

“Their motto, as I’m sure you have heard, is ‘never get high on your own supply.’ They are in it only for the money. Unfortunately if one addicted person happens to be selling drugs and getting ten more people addicted along the way, he is also part of the problem and should be held accountable.”

I disagreed with him, but decided I wouldn’t get much done continuing an email exchange with an anonymous Westchester dad. I forwarded him a couple links to harm reduction coalitions and called it a night. He never got back to me.

I disagreed with him, but decided I wouldn’t get much done continuing an email exchange with an anonymous Westchester dad. I forwarded him a couple links to harm reduction coalitions and called it a night. He never got back to me.

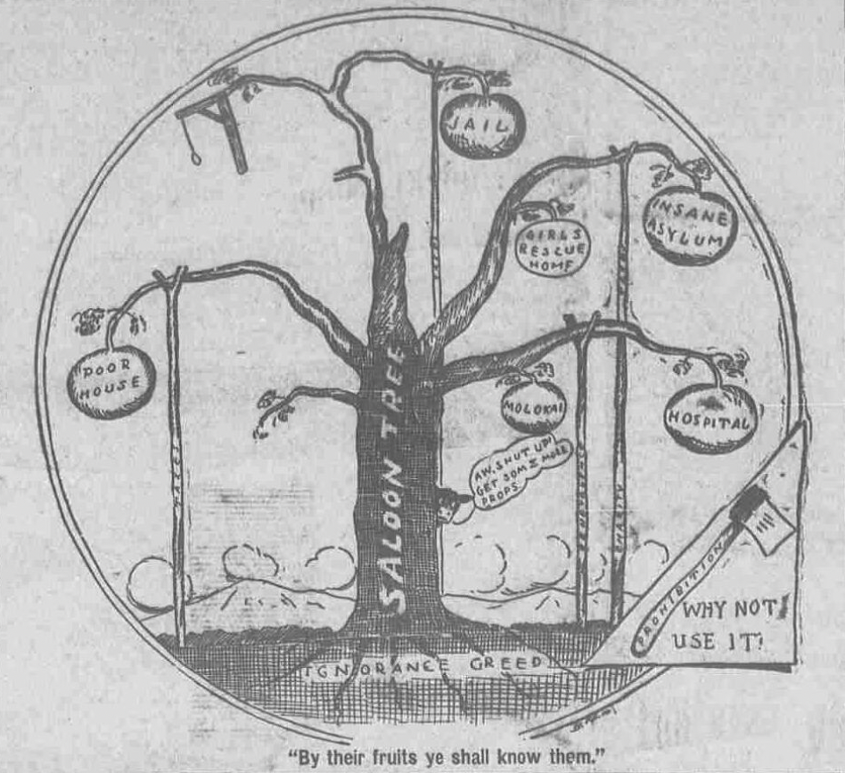

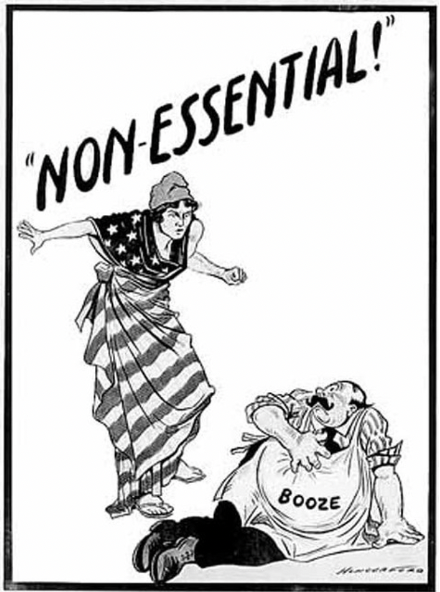

Still, I couldn’t get the exchange out of my head and started doing research into American anti-drug legislation and related propaganda. There’s a version of this flyer all over America, across time and space – a symptom of moral panic and subsequent effort to legislate what could be seen as Puritan values. Some of the qualities enmeshed in our country’s history are self-discipline, hard work, and a forced relationship with God to remedy sinful actions.

To put it more simply, we’re obsessed with the dichotomy of “bad” and “good,” which can be seen clearly in American drug-scare propaganda. Another thing enmeshed in our country’s history is racism and the way we speak in public about drugs and drug users/dealers is proof of this.

American Drug-Scare Propaganda

Below you’ll find just a few of the many examples of propaganda spread across the nation and some associated legislation.

Note: the totality of anti-drug messaging in the media is directly connected to a large rabbit hole now commonly called “the war on drugs,” a term coined by President Richard Nixon.

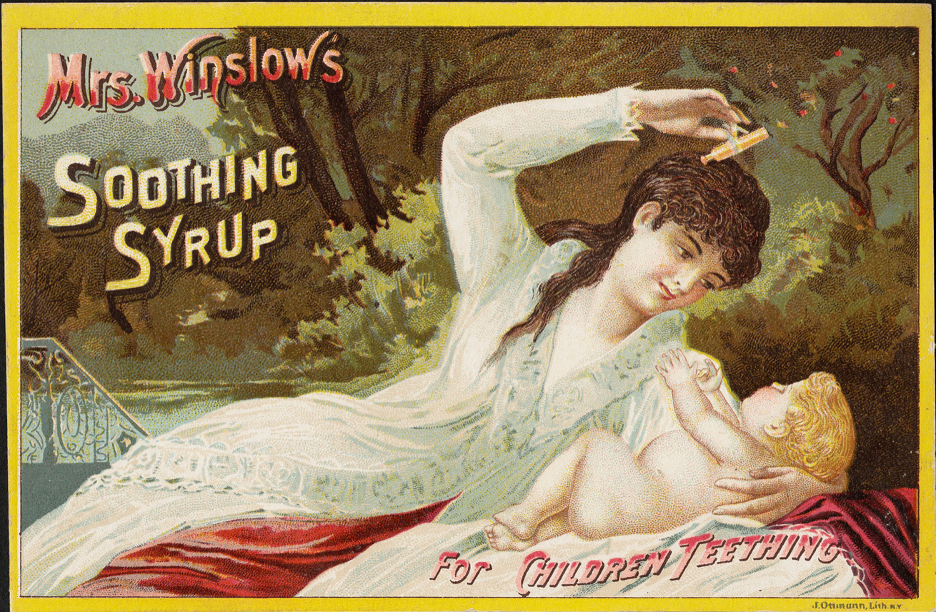

There was a time when American citizens of all social classes used drugs freely – various tonics prepared in the early 1900s contained cocaine and opium and people consumed these without fear of regulations or consequences. Those who became addicted to these drugs or overly misused them were seen sympathetically and as deserving of help, not persecution. The war on drugs did not begin as a war, but instead was seen as a public health issue. It wasn’t until White Americans recognized that people of color were using drugs that regulations began to tighten.

On the West Coast, smoking opium (originally an activity enjoyed by all) was made a criminal offense once Chinese workers immigrated to California and began working hard for very little pay, some smoking opium in what little free time they had. This perceived “threat” to White American job opportunities increased racialized rhetoric, and as China dealt with their own wave of opium addiction, they too wanted restrictions placed on the narcotics market. In order to maintain favorable trade relationships with China, America had no choice but to follow suit.

The main proponent of these restrictions in the United States was Hamilton Wright, US Opium Commissioner, but he was unable to garner much support for passing any restrictive legislation until he played into racial stereotypes of Chinese immigrants and Black people. When White Americans began to worry about their safety because the government told them that Chinese and Black people using drugs would hurt them in some way, support for the regulation of narcotics went up. This is when the Harrison Narcotics Act was introduced, on December 17, 1914.

The Harrison Narcotics Act

“An Act To provide for the registration of, with collectors of internal revenue, and to impose a special tax on all persons who produce, import, manufacture, compound, deal in, dispense, sell, distribute, or give away opium or coca leaves, their salts, derivatives, or preparations, and for other purposes.” (Naabt)

Prohibition

The passage of the 18th Amendment banned the manufacture, transportation, and sale of liquor, but said nothing about actually drinking it. Underground distilleries and saloons supplied bootleg liquor to an abundant clientele, while organized criminals fought to control the illegal alcohol markets. The mayhem prompted the U.S. Department of the Treasury to strengthen its law enforcement capabilities, as crime indeed went up and prominent gangsters like Al Capone rose to fame.

Prohibition Repealed

In 1933, the 21st Amendment returned control of liquor laws back to individual states, who could legally bar alcohol sales across an entire state, or let towns and counties decide to stay “dry” or be “wet” and allow the sale of alcohol. Fun fact: public bars weren’t allowed in Kansas until 1987!

But the end of Prohibition did not spell the end of anti-drug propaganda in the United States, as there was much more to come.

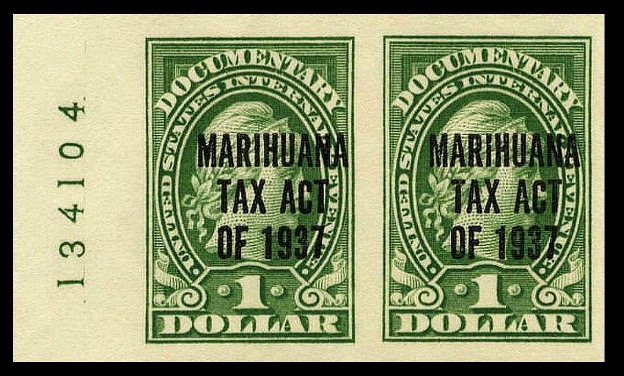

Anti-Marijuana

The Marijuana Tax Act was introduced in 1937, under which the importation, cultivation, possession and/or distribution of marijuana were regulated. This was backed by the essential anti-marijuana voice of the time, Harry Anslinger. Anslinger was Commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and already a proponent of banning alcohol.

He believed marijuana made people act absurd. Once prohibition was repealed and there was less of a focus on alcohol, he needed to target a new drug. Since marijuana was so popular, targeting it meant a never-ending stream of money into the bureau. Anslinger remained commissioner for 3 decades by disseminating sensationalist scare tactics – linking violent crimes to marijuana even though there was no science supporting his claims. Even when he looked for medical testimonies, he ignored all of the doctors telling him his fears of marijuana induced violence were irrational. He also hated jazz music and even went so far as to harass musicians who used drugs, such as Billie Holiday (who died handcuffed to her hospital bed because of Ansliger’s legislation). At the same time, he was kind to White people who used drugs, such as Judy Garland.

This relationship with the plant formed in direct contrast to historical attitudes, as people were largely unconcerned with marijuana (once spelled marihuana), and American industry profited off hemp fiber, seeds, and oils.

The War on Drugs

1971 brought about the Controlled Substances Act which placed all substances which were in some manner regulated under existing federal law into one of five schedules. AKA, some drugs are more evil than others. This was a direct pushback to the freewheeling attitudes of the 1960s, when experimentation with drugs and sex shocked traditional “normal” Americans.

The images below are screenshots from the film Curious Alice (1971) which was supposed to be an anti-drug education film and public service announcement. Created by the Department of Health, this film “portrays an animated fantasy based upon the characters in “Alice in Wonderland.” The film shows Alice as she toured a strange land where everyone had chosen to use drugs, forcing Alice to ponder whether drugs were the right choice for her. The “Mad Hatter” character represents Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD), the “Dormouse” represents sleeping pills, and the “King of Hearts” represents heroin. Ultimately, Alice concluded that drug abuse is senseless.”

Perhaps the release of this film around the same time as the Controlled Substance Act was an attempt to indoctrinate beliefs about inherent “evilness” of certain substances into the American public. During the same year, President Richard Nixon declared a “War on Drugs” which is a term still used today. He set the scene for greater legislation and surveillance of drug activity and the Reagan administration followed in his footsteps, reprioritizing the drug epidemic as our nation’s “number one enemy.” But the substances were never the real enemy… One of Nixon’s top aides, John Ehrlichman, had this to say:

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

– “Legalize It All” by Dan Baum, Harper’s Bazaar (April 2016)

“Just Say No”

It was in 1982 that first lady Nancy Reagan popularized the slogan “Just Say No” during the mass drug hysteria of the 80s which in turn led to higher incarceration rates.

During the Reagan years, prison penalties for drug crimes skyrocketed, and this trend continued for many years. In fact, the number of people incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses increased from 50,000 in 1980 to more than 400,000 by 1997. Incarceration isn’t really a solution here, as many continue to use and sell drugs in prison. Not to mention there is a higher risk of overdose right after being released from prison, as many end up re-entering an environment where they lack economic, emotional, physical, and social support.

Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign inspired the D.A.R.E. program, which was found to have little to no effect on drug use. Those who attended grade school between 1983 and 2009 most likely participated in D.A.R.E., myself included. The only thing I remember about it was we all had to pass around a stuffed animal lion “mascot” for some reason and thinking how unsanitary that was. I wished they would wash the lion but each time the D.A.R.E. officer showed up, the lion looked dirtier. A few years later, I heard that our D.A.R.E. officer received a couple DUI’s. D.A.R.E. cost taxpayers an estimated $600 million to $750 million per year in the 1990’s alone, and continued costing Americans even after the scientific studies came out disproving the program’s effectiveness. Today, an attitude of “just say no” is still prominent, even though more prevention programs are moving away from using scare tactics, and moving towards promoting peer interaction, cultural awareness, and critical thinking.

Maybe ODAD was aware of all of this history, and was trying to attack drug dealer’s morality instead of drug user’s – a “save the children” technique with a little shift of blame, but still ultimately under the umbrella of alarmist scare tactics with a comparison to slavery (maybe for shock value?) However, based on his email I tend to think he does believe anyone associated with drugs is part of the problem and many follow this train of thought. We’ve been criminalizing people in America who are associated with drugs, sometimes giving prison sentences meant for prominent drug dealers and manufacturers to citizens charged with minor possessions. Yet, people are still using drugs – they probably always will – but people of color experience the consequences of human’s tendency to use drugs at disproportionate rates.

It seems that a common thread in propaganda is equating two things seen as morally wrong, for greater emotional effect. If anti-drug propaganda isn’t racist, it’s moralizing. Or it’s both. Obviously, slavery was morally wrong, and if slavery is being compared to drug use and drug dealers then those things must be morally wrong too. Then no morally sound human can disagree with the messaging, right? This reduction of slavery to a buzzword in an attempt to further anti-drug propaganda is an exploitation of Black people’s history in America. Instead of allowing slavery to exist on the timeline of events with its own horrible history, it’s used to prop up somebody else’s ideas about a separate topic on a lime green piece of printer paper. It isn’t fair or accurate. It’s just another narrative used to portray someone’s moral beliefs as fact, similar to a lot of American legislation.

I can’t help but think these narratives all trickle down, weaving through various subcultures, perhaps in different words and phrases, or perhaps many the same.

The “war on drugs” has its own history which can be recognized without all the catchy phrases, biased PSAs, and conservative rhetoric. It’s a huge problem that any random person sees themselves as qualified enough to evaluate someone’s behavior as “good” or “bad” and that qualifies as a conversation about the drug epidemic.

PSAs don’t work to scare people straight. They just scare people. All this hype prevents people from getting the help they need and lands more people in jail.